History of Malbork Castle: From the Teutonic Knights to the Second World War

Malbork Castle has a long and rich history that makes it deserving of its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The 13th-century castle is located in the town from which it received its name and is the largest brick complex in Europe. Seeing the likes of major historical figures, including Polish kings, Napoleon Bonaparte and even the Führer himself, Malbork Castle has withstood the test of time and remains one of the most intriguing structures of the Middle Ages.

Malbork Castle was built by the Teutonic Knights

The Order of the Teutonic Knights was a Catholic religious society comprised of crusaders who fought against the pagan Prussians and the Christian Kingdom of Poland.

Following their success during the Prussian Crusade, they began work on a fortress they called Marienburg, after Mary, the mother of Jesus, in the city of Malbork. This was their attempt at strengthening their control over the area following the 1274 suppression of the Great Prussian Uprising.

Over the course of several decades, and during the Knights’ further conquests, the complex was expanded the accommodate the growing number of members residing there, with approximately 3,000 “brothers in arms” living at the castle at its height.

Built along the banks of the Nogat, it eventually covered more than 20 hectares, making it the largest fortified Gothic structure in Europe. It was comprised of the High, Middle and Lower castles, as well as several additional buildings. It was encircled by rings of defensive walls.

Downfall of the Teutonic Knights

Malbork Castle’s location along the Nogat allowed the Teutonic Knights to accomplish three things: collect tolls from passing ships, turn the fortress into a trading hub under the Hanseatic League and establish a monopoly on the amber trade.

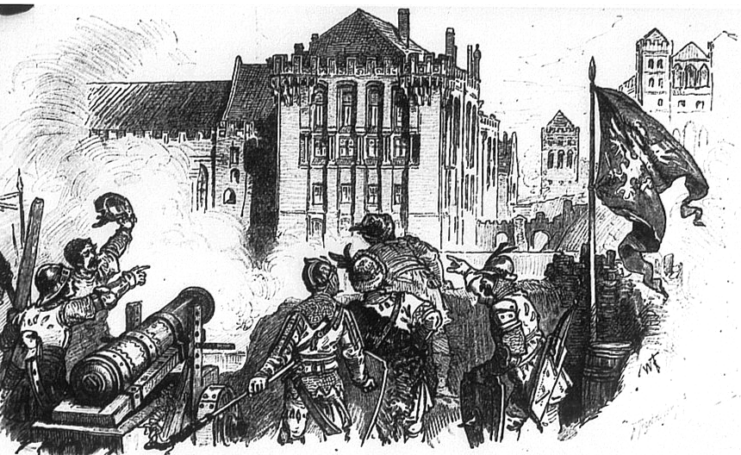

The Knights’ desire for conquest made them a frequent target, which led the fortress to be attacked during the Battle of Grunwald. Known as the Siege of Marienburg, the month-and-a-half-long assault ultimately ended in a victory for the Knights, despite them being greatly outnumbered by the Polish, Lithuanian and Moldavian troops.

While the Knights were able to hold power for a while, their control eventually waned. In 1456, during the Thirteen Years’ War, they raised taxes in the surrounding communities to pay ransoms for the cost of their wars against the Kingdom of Poland. This caused the public to oppose their rule.

Housing Polish kings

In 1457, Malbork Castle was sold to Polish King Casimir IV, who used it as one of several royal residences. It was also converted into Polish offices and institutions. For over 300 years, it served in this capacity, with the Swedish forces occupying it at points during the middle part of the 1600s.

The next major change for the castle came following the First Partition of Poland in 1772. This saw Malbork annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia and absorbed into the newly established province of West Prussia. This is when it began to fall into decline.

At this time, instead of being a place of order and importance, the fortress was converted into barracks for the Prussian Army. During the occupation, much of the decoration found within was destroyed, and places without military use were dismantled.

Reigniting public interest

In 1794, Prussian architect and head of the Oberbaudepartement David Gilly was given the responsibility of deciding Malbork Castle’s destiny. After a structural survey of the grounds, he was to decide whether to maintain it or to have it demolished. At his urging, the castle was designated a historical monument.

Gilly’s son, Friedrich, made several engravings of the fortress, brought them to Berlin and put them on display for the public to view, in the hopes of increasing the perception of Malbork Castle as a historical monument. His efforts were successful, with the public “rediscovering” the structure and the history of the Teutonic Knights.

During the Napoleonic period, Napoleon’s forces marched through Malbork, with the French military leader visiting the castle in 1807. He returned in 1812, when the Prussian Cossacks pushed back against the Grande Armée‘s march through the city. By the next year, the Cossacks had successfully taken the town back and set up the fortress as a hospital and arsenal.

Following the War of the Sixth Coalition between 1813-14, the castle had become a symbol of Prussian strength and history. This caused public opinion to move toward its preservation, and, in 1816, restoration officially began.

World War II saw Malbork Castle suffer extensive damage

In the early-to-mid 20th century, as the Führer rose to power, he took a liking to Malbork Castle. It quickly became a destination for Germany’s many youth organizations. He favored the castle so much that the structure served as the blueprint for the Order Castles, which were residential academies.

With the decline of Germany’s power over the course of the Second World War, Malbork Castle suffered severe damage, with over half of the castle destroyed. When the conflict came to a close, it was once again returned to Poland, where an organized effort was later initiated to restore it to its former glory.

While most of Malbork Castle has been reconstructed since the ongoing restoration began in 1962, there are still parts that show the damage caused during World War II. However, almost the entire complex has been preserved, and to this day it still remains the largest castle in the world by land area.