The Devastating Invasion That Kicked Off the Second World War

September 1, 2024, marks the 85th anniversary of the German invasion of Poland – and the beginning of the Second World War. Beginning with assaults from the water and on land, and heavily involving air support, the month-long engagement, which later came to include the Soviet Red Army, ended with the Eastern European nation being split in two and occupied for several years.

The following is a look back at the events that led-up to the invasion and the valiant defense put up by the Poles in the face of overwhelming odds.

Rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party

When discussing what led to World War II, the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party takes center stage.

The party capitalized on the economic turmoil and political instability that characterized the Weimar Republic following the First World War. The Treaty of Versailles had left the country with a crippled economy, a lack of military strength and a sense of embarrassment on the international stage, all of which allowed for the party’s rise, under the promise of returning Germany to its former glory.

When the future Führer was appointed chancellor in January 1933, it wasn’t long before he and his supporters began dismantling the democracy of the Weimar Republic. One way in which they did this was by passing the Reichstag Fire Decree following the Reichstag Fire that February. The law suspended civil liberties, including freedom of speech and of the press, and made it legal to arrest anyone who publicly went against the party.

By July 1933, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party was the only legal political entity in all of Germany.

How did European nations react to Germany’s political climate?

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party’s aggressive foreign policy became quite clear in 1936, with the reoccupation of the Rhineland (western Germany). This was followed two years later by the annexation of Austria and, later, that of the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. The latter was actually agreed upon by the likes of the United Kingdom and France, in the hopes appeasing some of the Führer‘s demands would prevent the outbreak of another war.

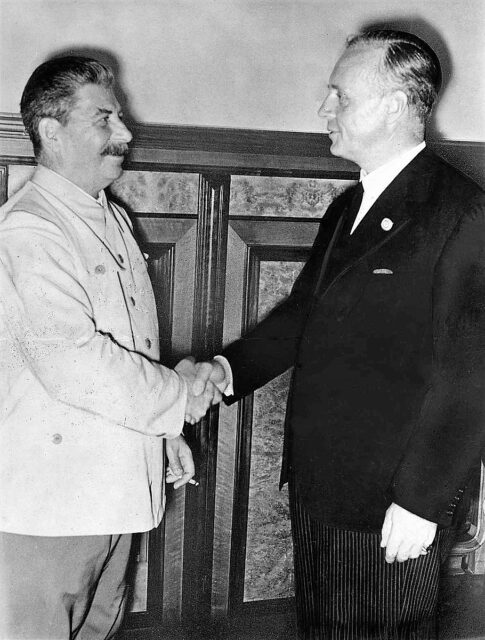

Not all countries were willing to give the Führer what he wanted, with many leaders suspicious of his motives. That’s not to say, however, that some didn’t use what was happening to their advantage. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, for example, signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, a non-aggression treaty that divided Eastern Europe between the USSR and Germany.

One of the stipulations under the agreement was that the eastern portion of Poland would fall under the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence, allowing Germany to invade the west and prevent the possibility of a two-front conflict.

Planning to invade Poland

Developed under the codename Fall Weiss (“Case White” or “Plan White”), the German invasion of Poland aimed to secure a swift and decisive victory through the use of infantry, air support and tanks. The hope was that such a fast attack would stop the Polish forces from regrouping, thus preventing them from mounting an effective defense and ultimately leading to their surrender.

Planned by several key figures within the German High Command, the operation required the invasion force be split into two main groups:

- Army Group North, led by Generaloberst Fedor von Bock.

- Army Group South, commanded by Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt.

They would move toward Warsaw from different positions, cutting off potential reinforcements from the primary group of Polish fighters.

September 1, 1939: Germany launches its invasion of Poland

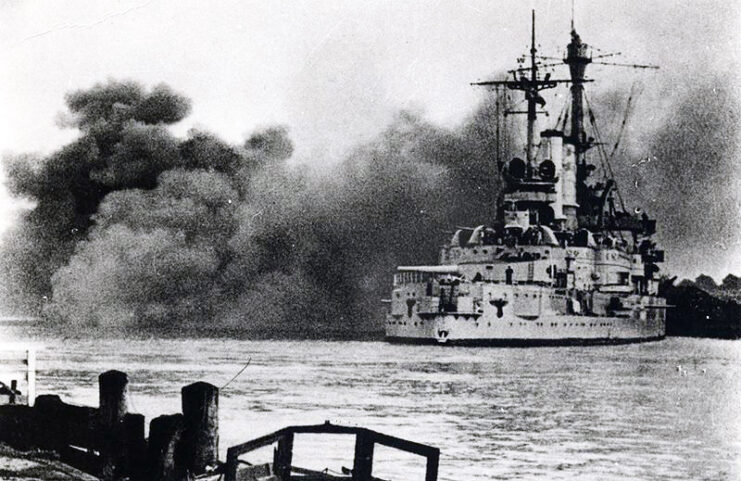

At 4:45 AM on September 1, 1939, the German battleship SMS Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Polish military outpost at Westerplatte, in the Free City of Danzig. These were the first cannon shots of the Second World War, and they marked the beginning of the German invasion. Simultaneously, ground troops crossed the border from the north, south and west in what was a coordinated assault designed to overwhelm Polish defenses.

The first days of the invasion saw battles take place at Mokra, Mława and the Bzura. While the former saw Polish cavalry inflict significant losses on the German 4. Panzer-Division, the sheer scale of the offensive soon began to take its toll on the Polish military as a whole. Much of the damage was done by the Luftwaffe, with pilots conducting relentless raids on both civilian and military infrastructure.

By September 8, German troops were on the outskirts of Warsaw, putting the capital under siege. At the same time, the Polish forces, split into disjointed groups, were launching whatever attacks they could against the invaders.

How did Poland attempt to defend itself against the German invasion?

Despite being outnumbered and outgunned (about 85 percent of Germany’s armored forces were involved in the invasion), the Polish military mounted a determined defense. While lacking the advanced weaponry and mechanized units of their enemy, the Poles were smart and used their knowledge of the local terrain to fight back.

Among the key military units involved in the country’s defense were the Armies Modlin and Łódz, the Kraków Army, and Armies Pomorze and Proznań.

Civilians also played important roles, forming partisan groups and supporting the military through other means. An example of this was the Polish Resistance, which, while unable to stop the advance, managed to not only delay it, but inflict many casualties. Another example of this resilience was the Battle of the Bzura from September 9-19, 1939, which temporarily halted the German advance, despite the Poles being defeated.

Unfortunately, these efforts weren’t enough, with the Germans overwhelming the Poles with their numbers and firepower.

September 17, 1939: Enter the Soviet Red Army

On September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, invaded Poland from the east. This caught the Polish troops off-guard and forced the already-beleaguered men to split themselves between the western and eastern borders of the country.

Joseph Stalin had justified the invasion by claiming he wanted to protect ethnic Belarusian and Ukrainian populations residing in the eastern part of the country. However, his real motivation was two-fold:

- Secure Soviet interests in the region.

- Prevent Germany from obtaining complete control of Poland.

With attacks coming from two fronts, it wasn’t long before the Polish forces became completely overwhelmed. By October 5, the last major Polish Army units, the Independent Operational Group Polesie (SGO Polesie), surrendered, marking the beginning of the country’s occupation.

Divided up between two European powers

Within a day of the last engagement of the invasion (the Battle of Kock, October 2-5, 1939), Poland was split between Germany and the Soviet Union. The former annexed the western and central portions of the country, while the USSR took control of the eastern region.

As with other nations that fell under enemy occupation during the Second World War, residents suffered regular mistreatment and persecution. The Germans implemented a policy of systematic extermination targeted at Polish political leaders, the intelligentsia and anyone viewed as a threat. The country’s Jewish population was also targeted. They were forced into ghettos, before being loaded into cattle cars and sent to concentration camps, where most didn’t survive.

The Soviet occupation of the east was equally as harsh, with mass deportations, executions, and the suppression of Polish culture and national identity; the aim was the Sovietization and Russification of the region. The Soviet secret police (NKVD), on Joseph Stalin’s orders, also committed the execution of over 21,800 military officers, political activists and intellectuals, in what became known as the Katyn Massacre – and that’s just scratching the surface of what occurred.

Despite the occupation, the Polish Resistance continued to fight. The Polish Underground State, a clandestine government-in-exile, coordinated efforts to resist the Soviets and Germans and regain some semblance of Polish independence. This resilience and resistance helped lay the groundwork for the nation’s eventual liberation and the re-establishment of an independent state following World War II.