Why Scientists Collected Radioactive Baby Teeth During the Cold War

When the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan at the end of the Second World War, a new era of nuclear weaponry was ushered into the world. While many believed that the use of nuclear force was justified to end the war, there were also those who were disturbed by the use of these weapons and became vocal advocates against them. Some were troubled about the ethics of the weapons, while others had concerns about the health implications that were yet unknown.

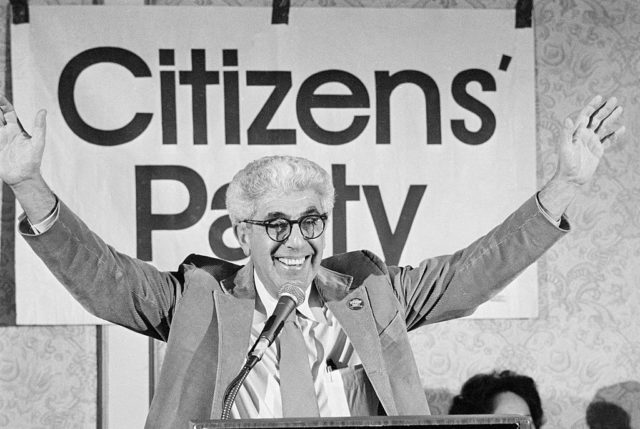

Among the latter were a group of scientists from St. Louis University and the Washington University School of Dental Medicine, who worked in coordination with the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information. Collectively, they wanted to determine the effects of nuclear fallout on humans. To do so, they collected children’s baby teeth to see how much radioactive material they contained.

Nuclear weapons testing in the US

The atomic bombs of the Second World War were only the beginning of nuclear weapon use by the US. After the war ended, testing continued which further increased public concern. One test in 1954 was strong enough to equal a blast created by 15 million tons of TNT and coated the surrounding islands with ash and radiation. As testing continued, so did concern over one particular isotope: strontium-90.

When it is naturally occurring it is nonreactive and nontoxic, but when produced as a result of nuclear fission, it becomes extremely concerning. As the American public became more aware of the testing and its fallout, concerns about strontium-90 made their way into the mainstream. Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson talked about the dangers of the isotope in the lead-up to the presidential election of 1956. Then, in 1959, radioactive deposits were found in wheat and milk in the Northern US.

Why baby teeth?

The Baby Tooth Survey used, well, baby teeth to determine how much strontium-90 they contained. This raises a question: why did scientists use baby teeth as part of their study, instead of looking for another way to test for this isotope? One of the reasons was that the isotope was especially harmful to infants and toddlers. And not only were baby teeth easy to access, but they were also from one of the groups that were going to be most heavily affected by this radiation.

In the mid-1950s, scientist and well-known pacifist Kathleen Lonsdale published in her book Is Peace Possible? that it was known that strontium-90 was easily absorbed in children and could lead to bone tumors. She also indicated that official reports from British and American sources showed that children in both countries had measurable amounts of the substance in their bodies.

The Baby Tooth Survey

When the study began, over 400 atomic tests had already been conducted above ground, and the concern was that strontium-90 was being absorbed by children through water and dairy. St. Louis was in a unique location for exploring this theory as there were many nuclear tests happening in Nevada, and the fallout was blowing east and falling on the farmlands around the city through the rain.

The team, consisting of scientists Barry Commoner and Ursula Franklin alongside physicians Eric and Louise Reiss, set out to answer whether or not the radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was being absorbed by children. They obtained the teeth for their study by reaching out to schools in St. Louis and encouraging children to mail them in. The children were incentivized with posters in the classrooms and buttons that read, “I gave my tooth to science.”

The results come in

The promotion of the study was extremely successful and the team gathered over 320,000 baby teeth throughout the 12-year span of the project. The study, without a doubt, demonstrated that children were absorbing strontium-90. The first stage of the study showed that there was a spike in the levels of the isotope in children born during the period following the commencement of heavy nuclear testing in 1953.

They found that among those children, the levels were highest in those who had been bottle-fed. They were then able to compare the teeth of children born in 1950 to children born in 1963, the former born before most of the nuclear tests were conducted, and the latter after. Those born in 1963 had a whopping 50 times as much strontium-90 in their teeth.

Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The study was so successful that the results, which were shared with President John F. Kennedy, played a major role in the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963. Dr. Eric Reiss presented the study findings to the American Senate committee, and two months later the treaty was signed by the US, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. It prevented explosions underwater, in space, or in the atmosphere.

It did, however, still allow for underground testing as long as the radioactive fallout stayed within the nation that conducted the test. It wasn’t until roughly 33 years later that a ban was signed to prevent all nuclear testing, including the kind previously allowed under the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

The impressive collection of baby teeth by the scientists involved in the Baby Tooth Survey was re-discovered nearly 20 years ago, and the slow process of data entry began, including note cards with information on each of the donors. The teeth were donated to the Radiation and Public Health Project with the hope that future scientists will be able to use the collection for other research, such as looking at fluoride and pesticide levels.