The Battle of Athens: When Armed Veterans Overthrew a Corrupt Local Government

When Bill White and his fellow GIs returned to their homes in Athens, Tennessee at the end of WWII, they were greeted with a welcome that was far from celebratory. Four deputies were waiting for them, arresting some of the men for public drunkenness, despite the fact that they’d had very few drinks. What White and his comrades experienced was, shockingly, nothing new. Their county had been dealing with this and other political corruption for nearly 10 years.

Although WWII was long over in August 1946, citizens of Athens and nearby Etowah decided to lead their own battle against corruption, brutality, and intimidation. On August 1-2 of that year, they engaged in what would later be called the Battle of Athens. A group, led by White and other veterans, decided to take matters into their own hands and address their grievances with their politicians by force.

Unhappy citizens

The root of this rebellion stems back to 1936 and the election of Paul Cantrell as the sheriff for McMinn County, where Athens and Etowah were located. He was reelected in 1938 and 1940, before being elected into the state senate in 1942 and 1944. In 1946, he again decided to run for sheriff. Throughout these 10 years he enacted a number of controversial policies, all of which contributed to the discontent among those in the county.

One of these unpopular policies involved a fee system under which the sheriff and deputies received a payment for each person they arrested. Many of them were tourists who, like White’s comrades, were questionably charged with drunkenness. Other questionable actions included introducing sketchy reelection tactics, such as halving the number of voting precincts and reducing the number of justices of the peace in the county.

During elections, Cantrell also orchestrated the intimidation of voters and allowed ineligible people to vote. The Department of Justice was aware that there were many allegations against him for electoral fraud but they took no action against it.

Targeting returning GIs

Cantrell and his men may have made one of their biggest fundamental errors when they started messing with the GIs who were fighting in, or returned from, WWII. During the war, two men on leave were killed by his supporters. News reached the men still overseas and, suffice to say, they were less than impressed.

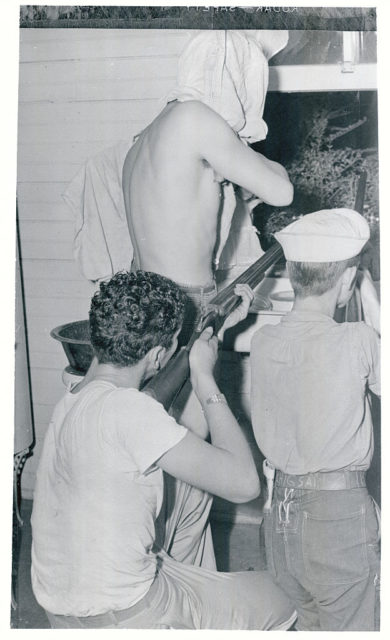

When the veterans returned to McMinn County, the deputies, in an effort to earn their wage fees, started harassing the GIs who they knew had money from being discharged. Apparently, White’s bus was not the only one stopped by deputies, as they would meet every busload of returning veterans and invent numerous reasons to take them to jail, just to put more money in their own pockets.

Once the men began integrating back into their hometowns, the deputies fined them for anything and everything they could, adding fuel to the fire. GIs totaled roughly 10 percent of the population of McMinn County and some of them decided they had had enough, creating their own political party to run against Cantrell and his men for various positions. The main opposition for the position of sheriff was Knox Henry.

Polling problems

Leading up to the 1946 election, Cantrell and his men made it as difficult as possible for GIs to register to vote or promote their party. Only one veteran voter registration book was provided for the entire county, and it conveniently went missing when GIs went in to use it. If the book was available, GIs were often arrested by deputies on bogus charges and their poll tax receipt, which was needed to vote, was taken from them. Candidates frequently received threats or their volunteers were attacked by deputies.

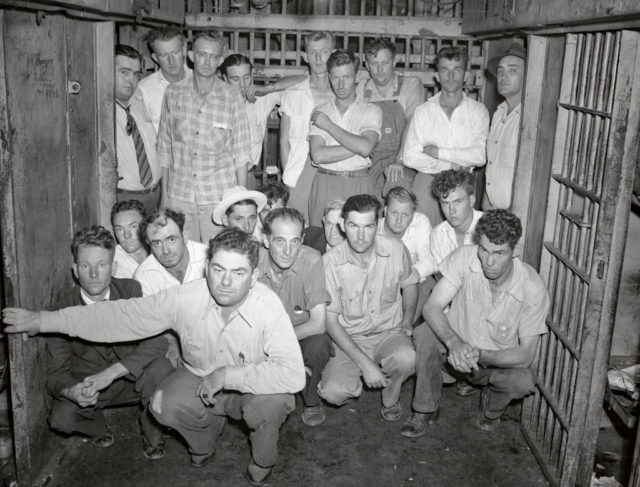

When polling day came around, citizens of McMinn County were greeted with the same corruption as in previous years. Voters had deputies watching them mark their ballots, deputies manned the doors of many polling stations, and one man, Tom Gillespie, was killed by a deputy after marking his ballot for the GIs and being told he couldn’t vote. Violence like this occurred at other polling stations as well.

The battle breaks out

Near the end of the day, Cantrell and his men took three voting boxes back to the jail before the official vote count, acting as the catalyst for the GIs to take action and start a rebellion. At this point, White ordered some of his men to go to the National Guard Armory, where they stole weapons to be distributed to GIs in preparation to fight and get the ballots back.

The GIs led a siege at the jail where the ballots were being held, demanding that they be returned. When the deputies in the jail refused, the GIs opened fire. Accounts of the battle vary, but what is clear is that the GIs knew they needed to win before the sheriff and deputies had reinforcements arrive.

While the GIs attacked the jail, other citizens in Athens took to rioting on the streets and targeting police vehicles, many of which were overturned. The battle finally came to an end when the GIs breached the jail and were able to obtain the ballot boxes that were still inside, beginning a count of the vote.

Aftermath of the Battle of Athens

With the ballots recovered and counted, the GI Non-Partisan League had a landslide victory: Henry with 2,175 and Cantrell with 1,270. They also won the positions of trustee, county clerk, and circuit court clerk. White was made a sheriff’s deputy, in part because he was seen as one of the few men who could lead the other GIs and manage any animosity they might have.

Despite the explosive nature of the rebellion, the GI party was able to take over with little difficulty, and Knox Henry became sheriff of the county. Although they were initially successful, the GI government didn’t last for long. When the GIs in McMinn County were contacted by other US veterans, they replied that shooting it out was not the most desirable solution to political problems.

Eleanor Roosevelt discussed the battle in its aftermath, calling it a “warning” of what could happen if citizens were denied the right to vote and indicating that perhaps GIs should be “re-evaluated” for violence before returning to civilian life. The election events also sparked political movements against GIs in several areas.

Eventually, however, media coverage of the event began to dwindle. On the first anniversary of the battle, the New York Times reported, “Today it appears that this political coalition of World War II veterans for direct action in community affairs, which many at the time regarded as a factor likely to develop nationally in the postwar period, was purely [a] local phenomenon in which veteran participation was incidental.”