The Short Career of the Civil War-Era Double-Barreled Cannon

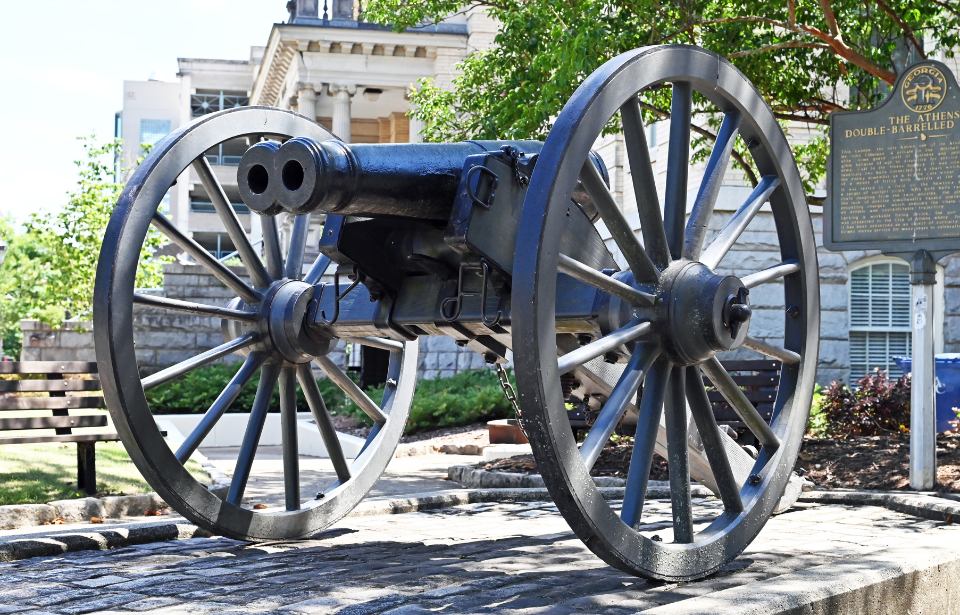

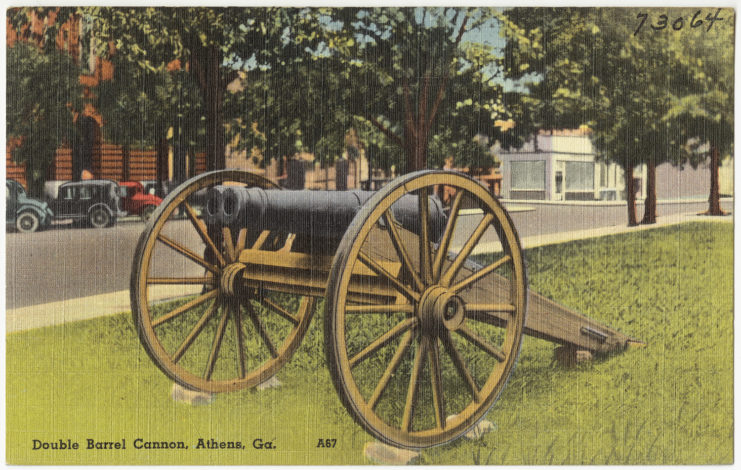

The double-barreled cannon is as cool as it sounds. It can shoot two cannon balls at the same time that, when attached by a chain, can plough through anything in their path. When the cannon was forged in Athens, Georgia in the spring of 1862, the hope was it would be adopted by the Confederate Army as a powerhouse weapon. While this wouldn’t be its fate, the double-barreled cannon remains a really cool weapon.

The double-barreled cannon’s design

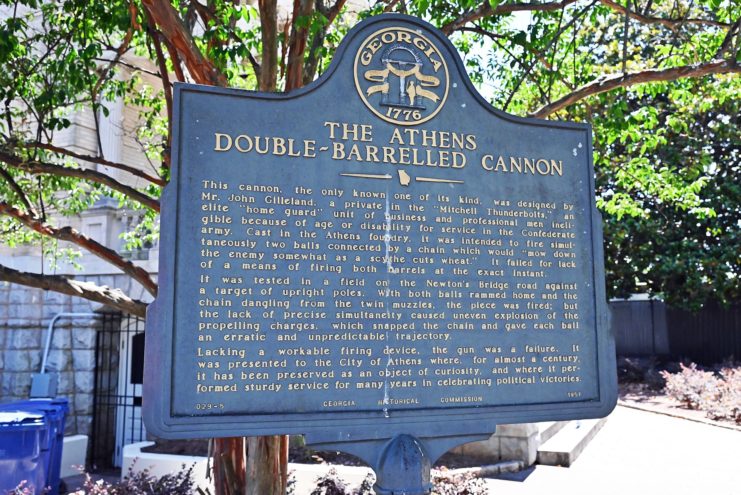

The double-barreled cannon was designed and forged by John Gilleland, a 53-year-old dentist and soldier in good standing with the Mitchell Thunderbolts. The money needed to produce the cannon was raised through a subscription fund, at a cost of about $350 per unit.

The cannon had two three-inch barrels that had a three-degree divergence, and was equipped with three touch holes to allow for separate and simultaneous fire. Although the weapon could fire single cannon balls, Gilleland intended for it to fire two six-pound ones connected by a 10-foot chain. The three-degree divergence ensured the shot would increase in length as it flew, causing the chain to fully extend as the cannon balls sped toward their target.

With this feature, the cannon could mow down groups of soldiers in a single shot.

Testing the double-barreled cannon

After the double-barreled cannon was built, Gilleland took it to a field north of Athens, near Newton Bridge, to test. Word had gotten out about the new weapon, and a crowd gathered to see what it was all about. Once he was satisfied with the location, Gilleland fired his test shots.

The first didn’t go quite as intended. The barrels didn’t fire simultaneously, so the balls and chain took an unexpected course. One observer recounted how “it [took] a kind of circular motion, plowed up about an acre of ground, tore up a cornfield, mowed down saplings, and [then] the chain broke, the two balls going in different directions.”

Despite its unpredictable course, the first shot proved the cannon could do a lot of damage. Gilleland fired additional ones, which were just as unpredictable. During the third shot, the chain broke almost immediately and both cannon balls took off in different directions. One destroyed the chimney on a nearby cabin and the other killed a cow.

Regardless, Gilleland was content with the damage caused and dubbed the test a success.

Denied by the Confederate Army

Following testing, Gilleland had the double-barreled cannon sen to the Confederate State Army’s Arsenal in Augusta, Georgia to undergo testing measures. Col. George Washington Rains was in charge of testing, and put the weapon through extensive use to see how it performed.

The results were less than favorable. Rain reported that the cannon was not usable, as it showed unpredictable rates of powder burn and barrel friction that caused the unpredictable performance of the weapon altogether.

Gilleland was outraged by the outcome of Rain’s testing. He wrote several letters to the governor of Georgia and the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, in the hopes they may reconsider the weapon for use in the Civil War. However, his pleas fell on deaf ears, and the double-barreled cannon was never adopted by the Confederate Army.

Instead, it was returned to Athens and placed in front of the town hall to act as a signal gun in case of an attack.

The double-barreled cannon’s only use in battle

Though the double-barreled cannon was not formally used by the Confederate Army, it did still see use. When Union troops were approaching Athens on August 2, 1864, the cannon, along with several other conventional weapons, was rolled out to the hill of Barber Creek. Here, it met with Brig. Gen. George Stoneman and his troops.

Grossly outnumbered, the Homeguard fired four shell barrages that included the double-barreled cannon’s shots. While the weapons themselves did little damage, the sheer noise they created caused the Union troops to withdraw.

Following the battle, the double-barreled cannon was sold and lost until after the Civil War. It was found in the 1890s, restored and returned to Athens, where it once again sits in front of the town hall. It’s pointed north, ready for any future aggression.