Winston Churchill Planned Britain’s Wartime Strategy In the Cabinet War Rooms

Air raid shelters and bunkers became commonplace in the United Kingdom during World War II. Under attack from the enemy during the Blitz, people moved themselves and their families to the safety of the underground. This occurred most in London, and the country’s prime minister wasn’t exempt from this precaution. Winston Churchill had his own secret bunker complex known as the Cabinet War Rooms.

Development of the Cabinet War Rooms

Although the UK didn’t declare war on Germany until 1939, plans for the Cabinet War Rooms were already underway three years prior. The Air Ministry realized that, in the event London was bombed, there would be significant casualties, and concerns arose for government officials operating outside of the city.

While it was decided in the coming years that most offices would operate from smaller areas near London, there was also a need for safe facilities within the city.

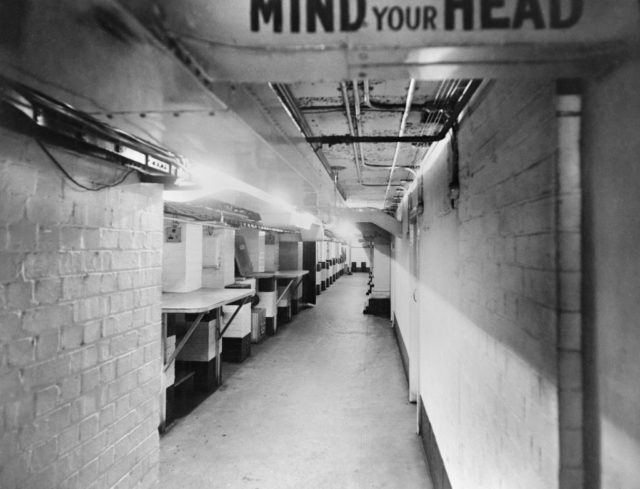

The basement of the New Public Offices (HM Treasury) was selected, and plans were drawn up for a Central War Room, where high-level government officials and members of the British Cabinet could safely stay in the event of aerial attacks. The basement was soundproofed and reinforced, and appropriate communications and ventilations systems were added.

The Cabinet War Rooms officially opened on August 27, 1939, just in time for the declaration of war. Little did the government know the complex would be at the heart of the country’s war effort, with 115 meetings held there by the time the conflict came to an end.

Use of the Cabinet War Rooms during the Second World War

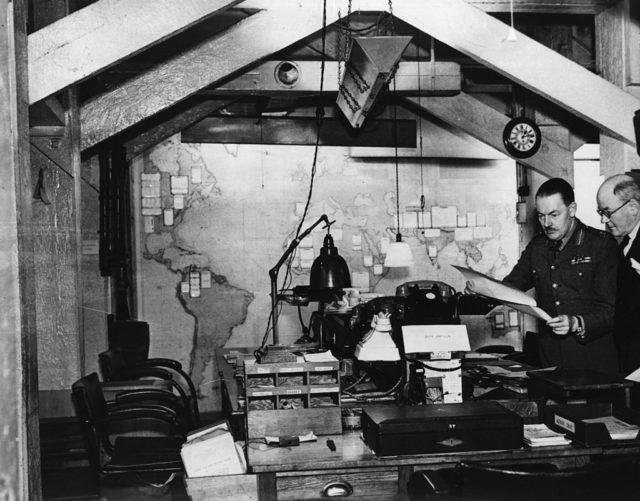

When Winston Churchill was made Britain’s prime minister in 1940, he visited the complex, declaring, “This is the room from which I will direct the war.”

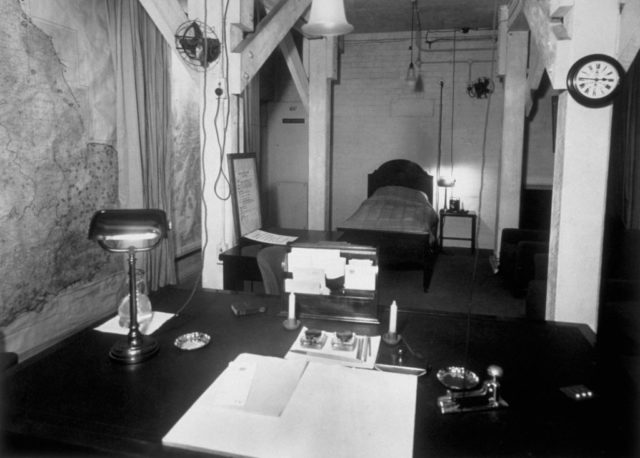

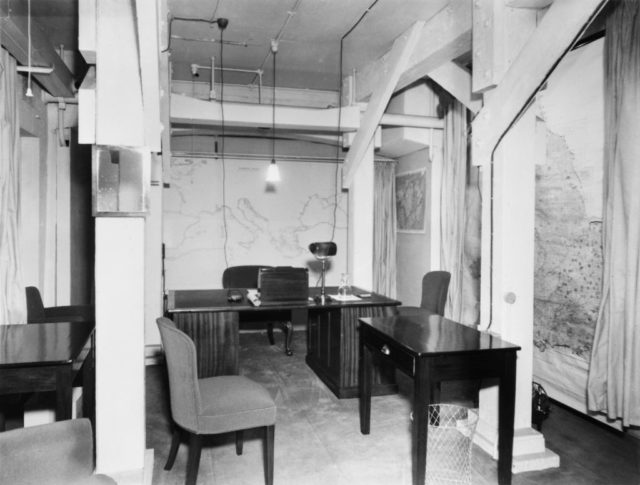

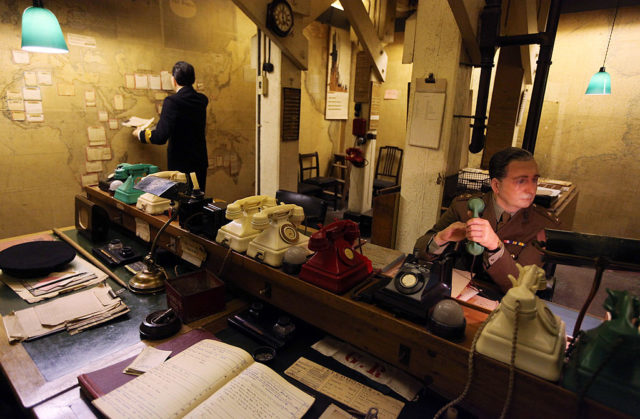

There was a dedicated space for Churchill, although he hardly ever slept there. He also apparently enjoyed watching air raids from the roof of the building. There was also a bedroom for his wife and staff, kitchens and, eventually, places for typists and telephone operators to work.

Throughout the war, many modifications and expansions were made. During the Blitz, a concrete slab was installed above to add further protection, allowing the Cabinet War Rooms to increase to three times their initial size.

Other additions included an encrypted phone line connecting Churchill to US President Franklin Roosevelt and equipment that allowed the prime minister to broadcast on the BBC. The complex was fitted with red and green lights, which indicated whether there was an air raid happening.

By the time it was fully outfitted, around 500 individuals worked and occasionally lived in the Cabinet War Rooms.

Abandonment following the Second World War

The Cabinet War Rooms were a hub of activity, and it wasn’t until August 16, 1945 that the lights were turned off, having been used non-stop for six years. When the Second World War came to an end, there was no longer a need for them and they were abandoned.

Although access to the complex was never outrightly banned, it did become by appointment only.

In 1948, a tour was organized for journalists, and in the following years the public could submit tour requests. As time went on, concerns arose that environmental conditions were ruining the historic documents that had been left behind upon the complex being abandoned, and discussions began over how to best preserve the historic site.

Adapted into a museum

In 1974, the Imperial War Museums (IWM) were asked to take over the site and turn it into something the public could more easily visit. This matter was pushed by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher when she took office, with an agreement made that the British government would provide the resources – financial and other – to make this a reality.

Thatcher was successful, and the Cabinet War Rooms officially opened to the public on April 4, 1984. The British prime minister was joined by members of Churchill’s family.

Initially, there were many rooms left out of the museum, but, in 2003, the bedrooms used by Churchill and his wife were restored and became part of the exhibit. They now hold permanent displays, detailing the management of WWII from the bunker, as well as brief histories of Churchill’s life.

There are also exhibits about what life was like in the complex, with rooms having been restored to period accuracy.